Case of post-intubation tracheal stenosis treated effectively with rigid bronchoscopic balloon bronchoplasty

Introduction:

Tracheal stenosis has widespread etiologies ranging from trauma, post-surgery, post intubation, inhalation injuries, congenital anomalies, auto immune diseases such as sarcoidosis, SLE, Wegener’s granulomatosis and Tuberculosis. Post intubation tracheal stenosis is relatively rare but a serious complication. It is considered as a late complication taking weeks or even months to develop after initial intubation. The risk increases as the duration of intubation increases. Patients may be erroneously diagnosed as asthma as they present with dyspnea and stridor. Surgical end to end anastomosis remains the standard of care, but not always feasible especially when patients are not deemed to be surgical candidates. Interventional Bronchoscopic procedures like rigid bronchoscopic dilatation, balloon bronchoplasty can play an important role in the management of tracheal stenosis of any cause. We present one of such case, where rigid dilatation and balloon bronchoplasty was performed for a case of post intubation tracheal stenosis in a 6-year-old child with grade 3 stenosis.

Case Report:

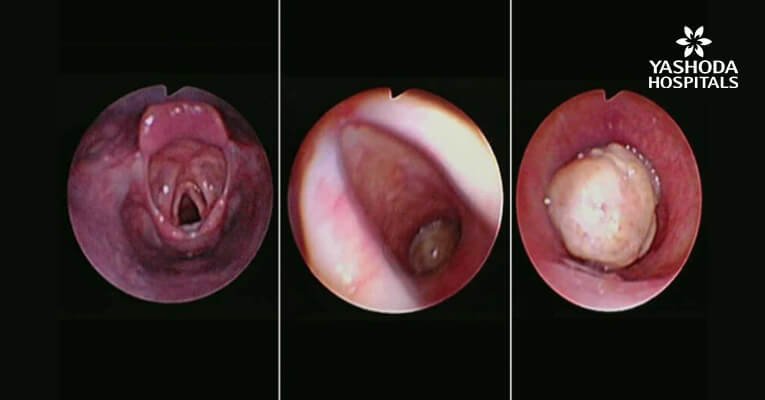

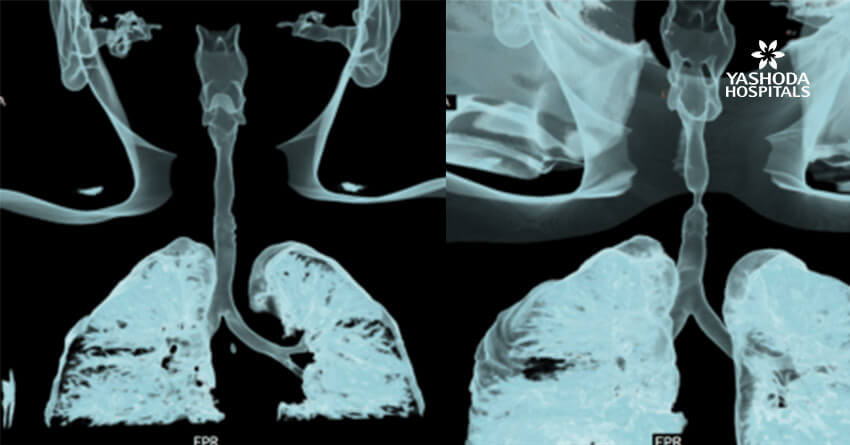

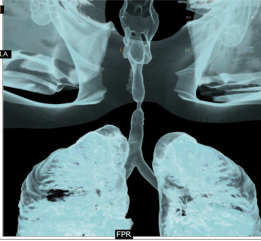

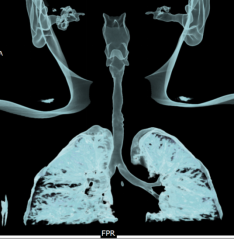

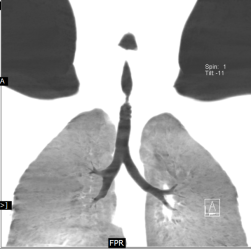

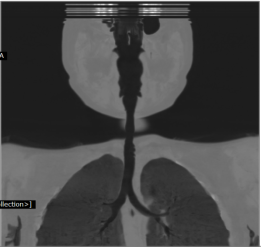

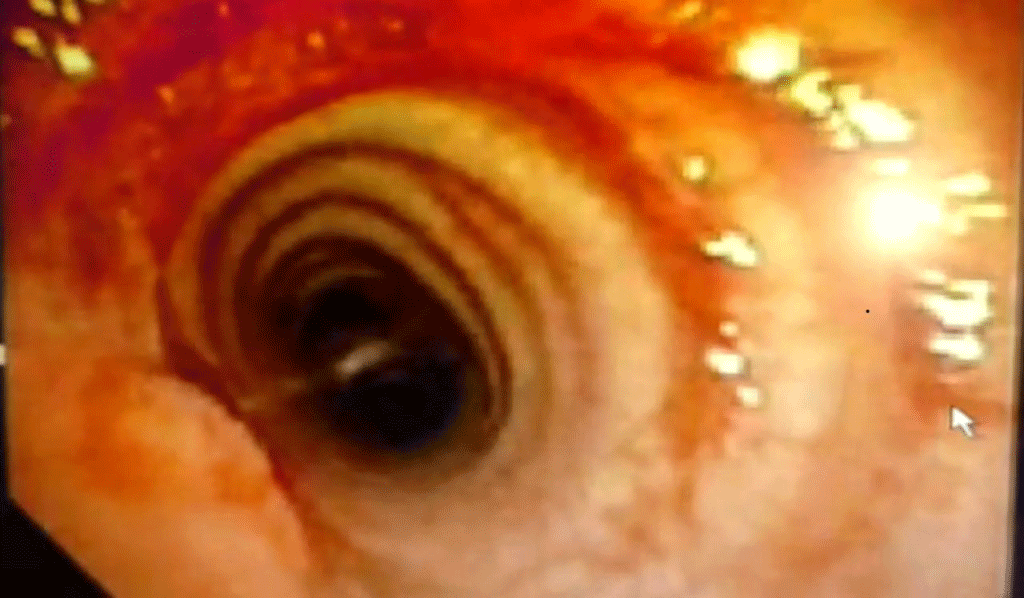

A 6-year-old female child presented to our clinic with progressive breathlessness and stridor for a duration of 5 days. She had a recent history of road traffic accident and sustained head injury and underwent craniotomy for extradural hemorrhage. Post-surgery she was on mechanical ventilator support for 10 days after which she was extubated. She developed stridor after 7 days of extubation. CT Neck revealed focal hour-glass configuration, concentric asymmetrical subglottic narrowing with associated soft tissue thickening 2-3cm below the level of vocal cords, with a diameter of 4.5 x 5.0 mm (AP X TR) at the point of maximal narrowing. Diagnostic flexible bronchoscopy showed circumferential stenosis (Grade III Myers-Cotton) of subglottic area about 2.5 cms below the glottis and we could not negotiate beyond the level of stenosis.

Rigid bronchoscopic repair of the stenosis was performed combining serial rigid bronchoscopic dilatations and balloon bronchoplasty using CRE dilatation balloons of varying sizes. Post dilatation, we were able to negotiate the rigid bronchoscope beyond the level of stenosis and were able to achieve a lumen of 100% with no residual stenosis. Follow-up CT Neck showed normal caliber of tracheal lumen with a luminal diameter of 8.6 x 8.3 mm at the level of previous narrowing. Total reduction of the clinical stridor was observed post procedure. Surveillance bronchoscopy after 4 weeks showed no further narrowing and good patency of tracheal lumen. Patient remained asymptomatic in subsequent follow up visits with improved pulmonary function tests

Discussion:

Stenosis of the larynx and/or trachea is a late complication of ETT placement taking weeks to months to develop after the initial intubation. The risk of developing stenosis is increased in those with prolonged intubation >7 days and is rare in those intubated for short periods (e.g., <3 days). The incidence is unknown, but reports range from 1 to 21 percent. Glottic (laryngeal) stenosis is thought to be due to pressure from the ETT itself, resulting in local tissue ischemia, inflammation, necrosis, and scarring. In support of this mechanism, inflammatory changes are seen in this region in as few as two to five days after intubation and most cases are in the posterior glottis and interarytenoid regions, where the ETT rests. Tracheal stenosis is caused by high ETT cuff pressure. When the ETT cuff pressure exceeds the mean capillary pressure in the tracheal mucosa (approximately 20 cm H2O), obstruction of capillary blood flow causes ischemia, inflammation, and erosion of the mucosa. This leads to necrosis, destruction of the tracheal architecture, and scarring.

Patients who are extubated may develop subacute or progressive dyspnea and/or or stridor while those who remain intubated (usually tracheostomized) may present with failure to wean from mechanical ventilation. Tracheal stenosis usually becomes symptomatic within five weeks after extubation, sometimes longer (e.g., months), and symptoms may become progressive over time. Stenosis may remain occult in a sedentary or deconditioned individual who is physically inactive. Pulmonology function testing may demonstrate fixed upper airway obstruction. If the patient remains intubated, a negative cuff leak test may support the diagnosis. Definitive diagnosis requires bronchoscopy or laryngoscopy, although emerging data suggests that spiral computed tomography (CT) with virtual bronchoscopy may be equally effective

Tracheal stenosis may require endoscopic stenting, balloon bronchoplasty, laser resection, or an alternative endoscopic intervention. Rates of success with endoscopic procedures are variable and restenosis is not infrequent. Mitomycin C (an antineoplastic agent) and steroids have been used anecdotally to prevent tracheal restenosis after local endoscopic therapies (e.g., laser resection or balloon dilatation), although randomized studies are lacking. Surgical resection is usually reserved for those with symptoms from extensive stenosis or those who fail endoscopic procedures. In contrast, stenotic lesions that involve the larynx are typically less amenable to endoscopic procedures and subspecialty consultation is advised.

More rarely, an obstructive fibrinous tracheal pseudo-membrane may cause tracheal obstruction and be responsible for extubation failure in such cases, fiberoptic bronchoscopy reveals a thick, circular, rubber-like membrane adhering to the tracheal wall at the site of the endotracheal tube cuff. Rigid bronchoscopic techniques are usually required for the removal of the pseudo-membrane.

Radiology Images:

Interventional Pulmonology

rigid bronchoscopic dilatation

balloon bronchoplasty

fiberoptic bronchoscopy

Bronchoscopic Images:

Tracheal Stenosis Before Dilatation

Post Procedure Luminal Patency

About Author –

Dr. Hari Kishan Gonuguntla, Consultant Interventional Pulmonologist, Yashoda Hospitals, Hyderabad

MD, DM (Pulmonology Medicine), Fellowship in Interventional Pulmonology (NCC, Japan)